Learn all about the power supply: modular and built-in devices that deliver electricity to the PLC backplane and modules, and learn the difference between control and field device power delivery.

Nearly every electronic device has some form of conversion from line voltage down to an appropriate voltage and form for its own use. Cell phones have wall outlet charges, desktop computers have the ATX supply, and industrial control cabinets almost always contain a DIN-rail mounted 24 volt DC supply.

PLCs also need a supply of electricity, but there are many different ways this is accomplished, and it’s also important to fully understand which devices they do NOT power.

PLC Power Supply Unit Types

For the sake of our discussion, we’ll combine the terms ‘power supply’ and ‘power input’ for these PLCs.

The ‘power supply’ is typically the trade name for the device that receives incoming AC line voltage and converts it down to 24 volts DC. On the other hand, a ‘power input’ is simply the screw terminals where power is applied. As we will see, all PLCs require some sort of power input, but not all PLCs contain a dedicated power supply.

We will explore all sorts of scenarios for PLC power delivery.

Built-in Power Supply Units for AC

Small PLCs, like the ones that contain all of the I/O points on the main unit, often have the power conversion built right in. We can recognize these by the AC line voltage names printed on the terminals: most commonly L and N, or L1 and L2.

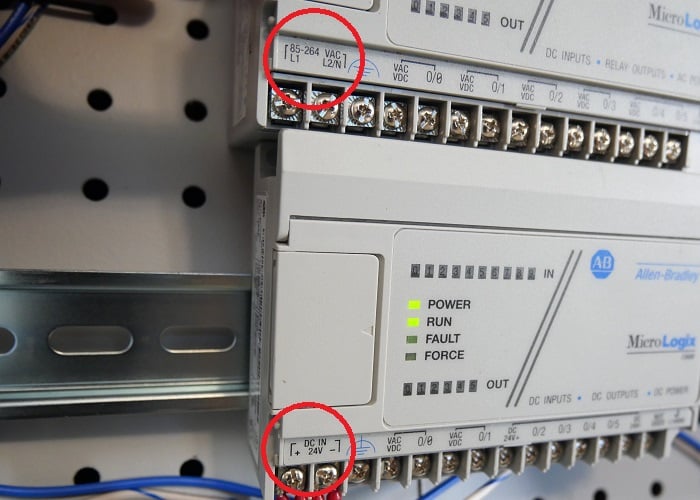

Figure 1. Two models of PLCs with AC inputs and a built-in 24 volt supply.

Often an AC input PLC would directly accept a higher AC voltage like 240 VAC, but be very, very careful as this can immediately destroy the PLC if it is only designed for 120 volts max.

The advantage of these systems is that they can be installed with no other power delivery equipment, and they usually contain their own 24 volt DC output for a few field I/O devices, although it won’t deliver very much current. All-in-all, it’s a great solution when you just need a small automation system avoiding the footprint and cost of extra parts.

Built-in Power Supply Units for DC

Those same small brick-style PLCs, as well as some of the smaller modular PLCs might also accept a direct delivery of DC voltage from an external power supply right into the CPU. From an outside look, they appear almost identical to the AC input models, but there will be two main distinguishing pointers.

First, the printing of the labels next to the terminals will be different, showing DC + and – instead of L and N. I wish I didn’t have to state such an obvious fact, but the reality is that too many PLCs have been destroyed by a careless technician swapping out a device with one that seems 100% identical. READ the labels.

Figure 2. Two different types of PLC power supply voltage: AC on the top model and DC on the bottom. Note the deeper size of the AC supply model.

Second, while the AC-powered PLCs contain their own embedded 24 VDC output, the PLCs that require DC already will not have such terminals. More on this in a moment. But it’s a caution to be aware of: if two terminals on the old PLC showed a DC output, but they are missing or labeled ‘NC’ on the new model, there’s a good chance you got a different PLC.

If these PLCs lack a DC output, why would you prefer this over a similar AC model that also provides the needed 24 volts?

The advantage appears in scenarios that require more current (output power) than those built-in supplies can offer. Your system might have a few motor contactors and solenoid valves that demand more power. A single well-chosen DIN rail power supply can feed the PLC and all the I/O devices, and we are back to just a single AC supply input, reducing the number of distribution terminal blocks and electrical hazards in the cabinet.

Modular Power Supply Units for AC

For larger PLCs, the power supply is usually separated from the CPU and attached to the backplane chassis or to an expansion pin header on the left or right side of the CPU module.

This style resembles those with the built-in AC supply, but the manufacturer will offer several different power output modules. For an expansive PLC with over a dozen modules, you may need to spend more to purchase a larger power supply, but it’s nice to keep it separate from the CPU so you don’t also have to upgrade that at a massive cost.

Figure 3. Two modular power supplies, an AutomationDirect Productivity power supply requiring DC (left) and a Mitsubishi PLC power supply clearly marked for AC (right).

These power supply modules will be similarly marked with L and N, or L1 and L2, and they might also have options for either 120 or 240 VAC. As with the built-in AC supplies, it is common to find a DC output also built right into these power supply units.

By providing various modular options, a custom PLC scenario can be easily designed with sufficient power for all modules, while also allowing optimum selection options for the rest of the chassis.

Unfortunately for those built-in PLCs, there is far less flexibility, and they only work for small automation systems.

Modular Power Supply Units for DC

This final method of supplying power to the PLC modules provides the flexibility of selecting one large external DC power supply for the entire system, while also providing a sufficient route for power to the entire PLC through the backplane.

These power supplies will be clearly marked for DC + and -, but they also attach to the far left side of the chassis or wiring harness.

Figure 4. An Allen-Bradley PLC power supply module requiring a 24 volt DC input.

It is important to note that the PLC power supply, whether modular or embedded into the CPU, only powers the CPU and the operation of the modules. It will not power the output terminals (loads) or the input devices (sensors and switches). How do you power those field devices? Good question…

Field I/O Power Supply

Even if your PLC is powered up with green lights on all modules, you aren’t automatically given power at the I/O terminal. In fact, I have never seen a PLC where the backplane power was delivered directly to the terminals, but such a PLC may exist out there somewhere.

In a few situations, I have seen a common ground between the input terminals and the backplane power supply, such that simply proving 24 volts to the terminal successfully registered a high signal. But even this is uncommon.

You must use a DC power supply, whether external or built-in, and route the +24 and 0 volts to the common terminals of the I/O modules. Be sure to understand how sourcing and sinking modules work. I have seen several PLCs where the program appeared to be working, but I/O signals failed to register at the PLC due to the common power or ground not completing the circuit to the power supply.

Providing Power to PLCs

It’s hard to say which part of a PLC is most important, but it’s safe to say that insufficient power delivery is a recipe for failure. Choose the right type and size of power supply, and you’ll have one less trouble spot–not just for the PLC, but for the entire automation system.

Copyright Statement: The content of this website is intended for personal learning purposes only. If it infringes upon your copyright, please contact us for removal. Email: admin@eleok.com